COVID Immune Suppression Genes

Categories: COVID Publications

Developing a new platform to identify viral genes responsible for immune suppression/invasion and applying it to COVID.

For posterity’s sake I am sharing a Tweet thread for the paper I was involved with High-content screening of coronavirus genes for innate immune suppression reveals enhanced potency of SARS-CoV-2 proteins:

Very excited to have been involved in this SARS-CoV-2 research that introduces new assays to detect viral gene immune suppression capabilities and even discovers a potential new gene overlapping with Spike.

— Trenton Bricken (@TrentonBricken) March 3, 2021

Read the pre-print here: https://t.co/8NAGIEgoAk

Thread 🧵 1/n

In case you would rather read the full text rather than the Tweet thread it is below:

Very excited to have been involved with some new SARS-CoV-2 research that makes the following contributions:

- Many SARS-CoV-2 proteins are discovered to have enhanced immune suppression compared to other coronaviruses including SARS-CoV-1 and MERS.

- A potential gene is discovered overlapping the Spike gene that shows immune suppression capabilities.

- A suite of high-content cell-based assays are introduced that can be used to rapidly characterize immune suppression of viral genes. These assays should be useful for pandemic responses and virology research more broadly. Read the pre-print here: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.03.02.433434v1

Diving deeper into the paper:

Viruses are cleared from the body unless they counter the innate immune system. The degree of that counteraction may help us predict the transmissibility and pathogenicity of future viruses. For instance, SARS-CoV-2 is more transmissible and often has weaker symptoms than SARS-CoV-1 or MERS. This might be explained in part by greater immune suppression by SARS-CoV-2 genes.

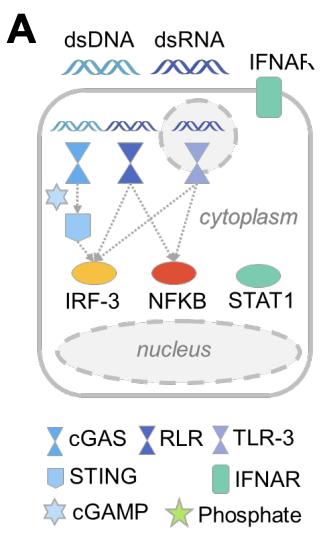

What are these immune responses? In humans, there are a number of intracellular signaling pathways responsible for detecting if the cell is infected. These pathways do things like tell the cell to kill itself (apoptosis) and warn other cells there is an infection.

This figure shows highly simplified IRF3, STAT1 and NFkB pathways. All of these are transcription factors that translocate from the cytoplasm into the nucleus to express the proteins necessary to respond to infection.

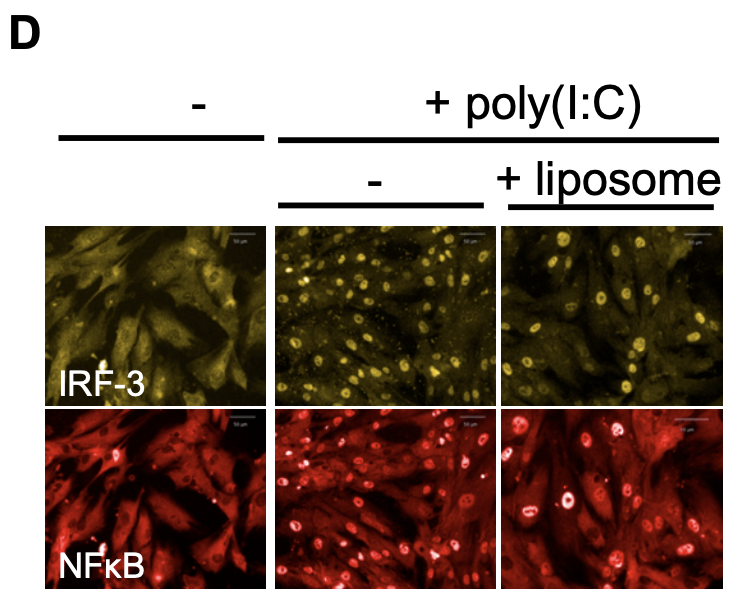

The first assay developed uses high throughput fluorescent microscopy to identify if a specific gene prevents translocation of the aforementioned transcription factors into the nucleus.

For example, see how for IRF3 and NFkB the left most column below shows these transcription factors fluorescing in the cytoplasm but not in the nucleus. Upon stimulation, in the middle and right columns these transcription factors translocate to the nucleus making them light up and the cytoplasm becomes darker.

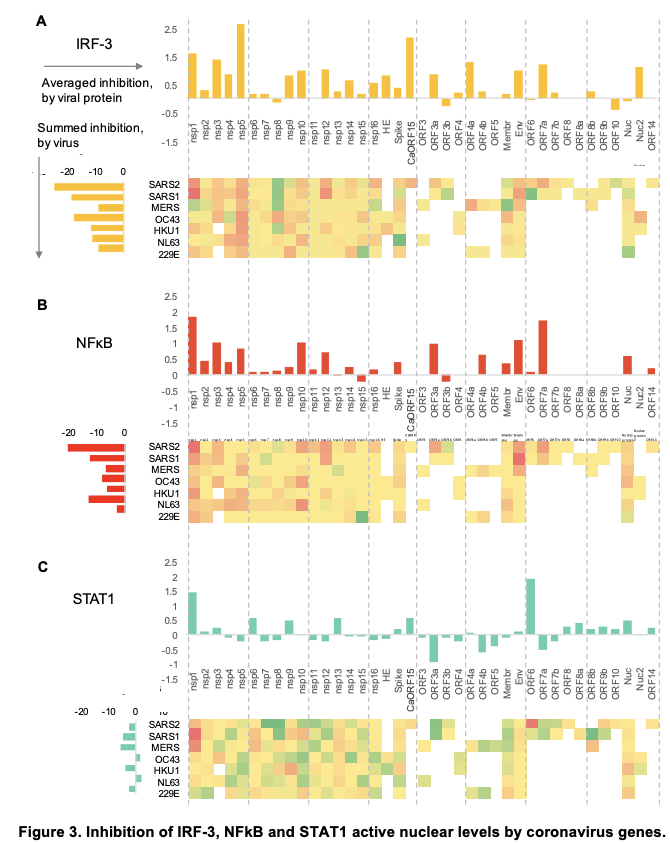

Using this approach we show for each gene across many different coronaviruses how much each suppresses the different transcription factors (in the heat-map red is reduced and green is increased translocation):

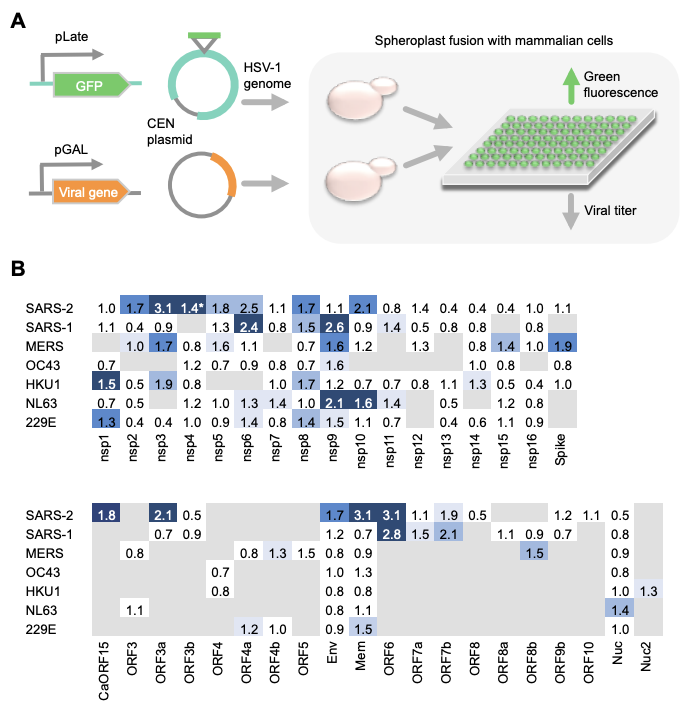

The second assay takes a very different (and super cool) approach to identifying immune suppression genes. One yeast cell expresses the Herpes Simplex Virus-1 (HSV-1) genome. Another yeast cell expresses the viral gene of interest. Both of these yeast cells are fused with a mammalian (HeLa) cell which will become infected only if the viral gene of interest is capable of immune suppression (see paper for more details).

This successful infection by HSV-1 is indicated by fluorescence. This protocol and its results for the different coronaviruses are summarized:

A final assay uses flow cytometry and the NFkB pathway specifically to further investigate how it is affected by the different genes (these results support the findings of the first assay outlined).

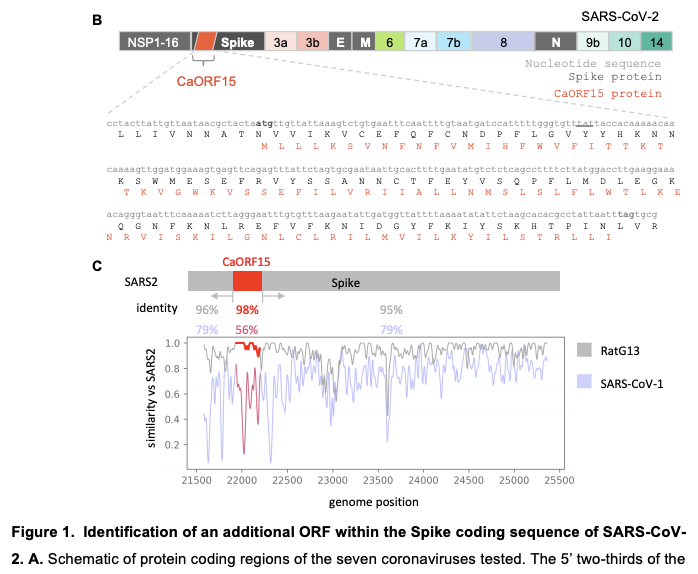

Moving on to the discovery of the putative novel SARS-CoV-2 gene! It is inside the spike protein, 87-AA long and in a different reading frame. It is found to be highly conserved with the bat RatG13 sequence and have IRF3 and STAT suppression.

There are two really cool things to me about the discovery of this gene. First, it is amazing just how optimized viruses are where their genome is capable of simultaneously encoding for Spike and an immune suppression gene (we know SARS-CoV-2 already does this in the N protein and ORF9b with leaky scanning).

Second, it is noted that Spike protein is used in all of our approved SARS-CoV-2 vaccines. For our DNA and mRNA based vaccines, encoding for Spike could also secretly encode for, and potentially express, this novel immune suppression gene. However, the exact Spike nucleotide sequence must be used for this novel gene to be encoded. For example, Pfizer’s vaccine is codon optimized in such a way that it does not encode for this novel gene. Moreover, it is very important to emphasize that the FDA approved vaccines have been shown to be safe and so in this case there are not any problems with whether this novel gene is expressed.

However, that we could in the future accidentally encode additional viral proteins hidden inside our vaccines does give support to smaller, epitope based vaccine designs of the sort I have been previously involved with. Rather than using the entire Spike protein that is 1273-AA long, we can hypothetically get even better population coverage with just a handful of epitopes of only between 8 and 25-AA long. Work showing these results: https://www.cell.com/cell-systems/fulltext/S2405-4712(20)30238-6

I am very grateful to have had the chance to play a small part in this work through contributing to image processing portion via a summer internship with the Marks (@deboramarks) and Silver labs. Thanks also to friends, mentors and collaborators @JCVenterInst, @harvardmed, @_nathanrollins, @joshuaerollins and funding from IARPA (@IARPAnews).

Consider reading the full paper as it contains a lot more details! Also note that this is a preprint. If you read the paper do send feedback. Doing COVID research is too important for mistakes to be made.

——> Paper: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2021.03.02.433434v1